Topic 6: Probabilistic prediction of storm surge and wave

Interview

It contributes to the design and optimal placement of coastal structures such as ports and harbors, and coastal protection structures against coastal erosion.

Coastal engineering also aims to forecast changes in coastal topography over time.

Some coastal areas are more vulnerable to high waves, while others are more susceptible to storm surges. My goal is to develop a method that can identify and predict the most severe hazard that might occur in each region after a typhoon has been controlled.

High waves and storm surges differ in terms of their oscillation period (frequency).

High waves are the familiar surface waves we often see at the beach, but it has a larger scale than them. High waves are wind-driven and typically have periods ranging from a few seconds to several tens of seconds.

In contrast, storm surges are much longer-period phenomena. They occur when prolonged winds or drops in atmospheric pressure from a typhoon cause the sea level to rise.

This rise is due to mechanisms such as “wind-driven surge”, where water piles up at the back of a bay under prolonged wind, or “pressure-driven surge”, where low pressure causes sea level rise by atmospheric suction.

When a typhoon approaches, both wind and pressure fluctuations generate storm waves and surges.

We need to be able to predict both of these phenomena and evaluate how and when they may impact the coastline, potentially causing inundation.

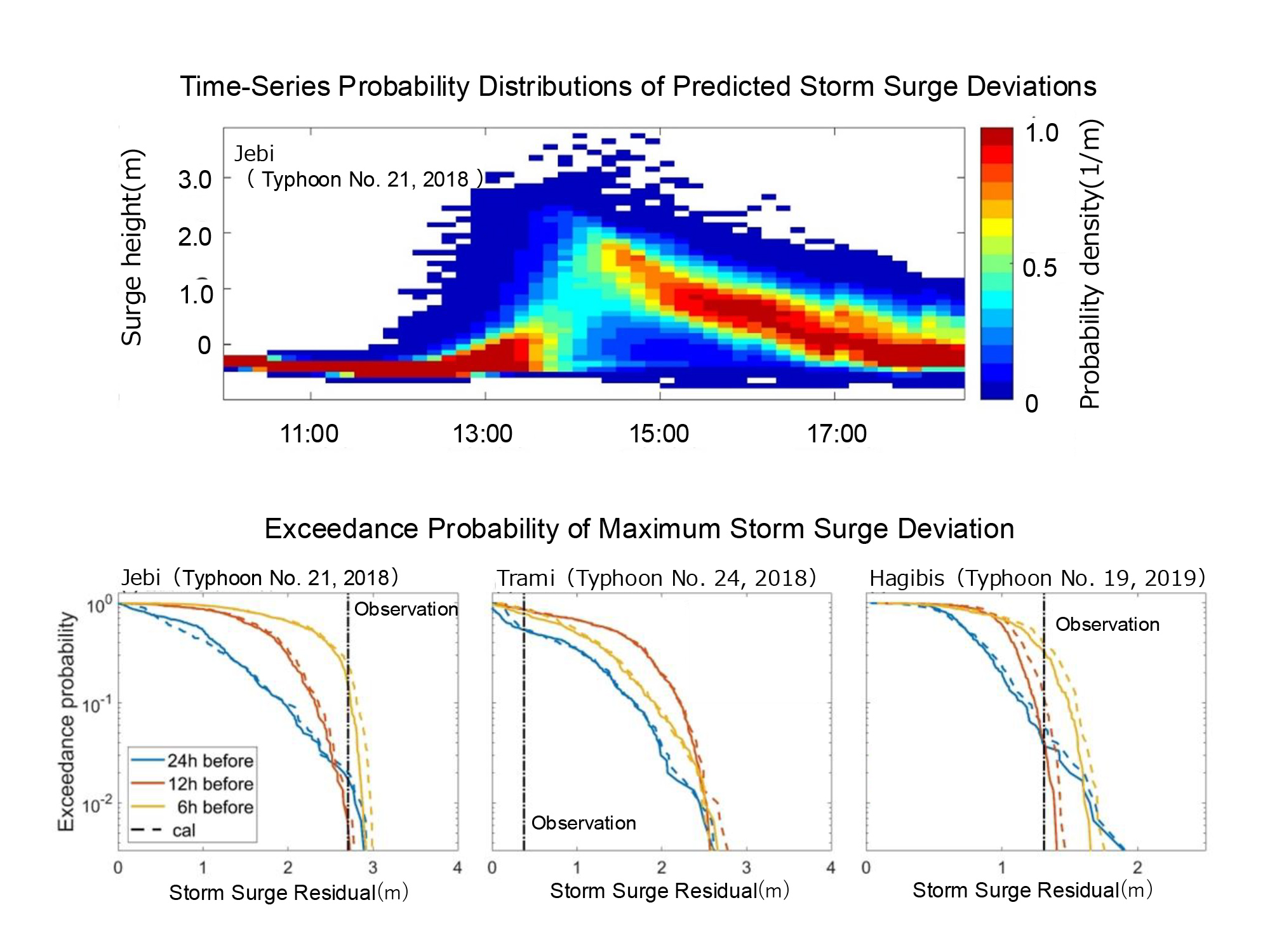

Figure:Example of Applying a Probabilistic Storm Surge Deviation Forecast System

Probability distributions of storm surge deviations at each time point (top) based on forecasts made 6 hours before the landfall of Typhoon Jebi (Typhoon No. 21, 2018).

From these results, the exceedance probability distribution of the maximum predicted storm surge deviation (bottom left, 6 hours before landfall) is derived.

Similarly, the bottom center and right panels show the exceedance probability distributions of the maximum predicted storm surge deviations for Typhoon Trami (Typhoon No. 24, 2018) in Osaka Bay and Typhoon Hagibis (Typhoon No. 19, 2019) in Tokyo Bay, respectively.

All distributions include the actually observed storm surge deviations, but the corresponding exceedance probabilities vary.

This suggests that even for a single typhoon forecast, the storm surge prediction can either overestimate or underestimate the actual surge.

Based on those predictions, we can then optimize the control strategies themselves.

Given the limited lead time before a typhoon impacts the coast, it is crucial to compute coastal hazards quickly and efficiently.

We must also consider uncertainty—rather than relying on a single deterministic scenario, we assume that even after typhoon control, multiple possible outcomes could emerge.

This means we must evaluate hazards across several scenarios at high speed and with adequate precision.

As I mentioned earlier, storm waves and storm surges are governed by different mechanisms.

Storm surges are primarily determined by how much the wind blows and how the pressure changes over time in enclosed areas like bays.

In contrast, high waves can originate far offshore and propagate over long distances to reach coastal locations.

So, even if we control the same typhoon, the effects on storm surges and high waves can differ greatly.

For high waves, the wind field over a broader region and longer time span—including before control—may need to be considered.

Depending on the conditions, waves generated in the open ocean may take several days to reach the coast.

While tsunami waves travel at high speeds proportional to the square root of the water depth (often compared to jet aircraft), wind-driven waves have slightly shorter periods and travel at speeds determined only by their period in deep water.

Their propagation speeds are generally around 100–200 meters per second.

When the wave speed matches the typhoon's translation speed, high waves can intensify.

This is because the waves stay under the influence of strong typhoon winds longer, continuously receiving energy and growing larger.

Not just wind speed, but also the duration, fetch (wind travel distance), and propagation distance of the waves all combine to determine wave height.

All these factors must be incorporated into hazard prediction models.

For example, waves with periods that fall between those of high waves and storm surges can occur, and these can cause localized inundation even along what appears to be a straight coastline.

Ideally, such intermediate-period waves should also be included in our predictive models.

In the long term, coastal topography is also highly dynamic, changing over time.

So, in addition to the inherent uncertainty in typhoon forecasting, we must continuously update predictions to reflect changing land use and coastal morphology—and that is a significant challenge.

By 2050, I hope we will have built systems capable of forecasting what kind of hazard will occur, where, and with what probability—as early, efficiently, and accurately as possible.

Such systems will be crucial to effectively mitigate the coastal risks associated with typhoons in a changing climate.